A Postmortem on River Niger Dredging: Sir Isaac Chuks x-rays the state of Nigeria’s Dredging Industry

By Edmund Chilaka / 4th Quarter 2012

Although Sir Isaac Chuks is now clearly a doyen of Nigeria’s dredging industry, he got involved in dredging by circumstance. He had been in civil construction under the wings of an originally Chinese company by the name of Funq Tai. Funq Tai had been formed in Taipei back in the 1970s and the ebullient young Nigerian in the midst of Oriental business gurus managed to steer the company to serve Nigeria’s oil and gas industry during its relative infancy. That was the late 1970s when Nigeria was building a refinery in Kaduna and laying pipelines to take petroleum products to the northern parts of the country. Funq Tai played a major role in that huge project which involved laying 3,000 km of pipeline from oilfields deep in the Niger Delta to Minna and surrounding locations. Working with another of his companies, Chuks International, Sir Chuks was responsible for transport and logistics needed by thousands of construction workers and for moving tons of building materials to the field. The main contractor, Chiyoda, depended on the efficiency of Chuks International to achieve its targets. Thus, the refinery was commissioned on schedule by President Shehu Shagari in 1980.

Subsequently, Sir Chuks got the franchise to run Funq Tai in Nigeria. It was in his next project, however, that he came face-to-face with the dredging industry and the intricacies of using dredged materials, principally, sand. The NNPC Jetty in Apapa port was due for an upgrade arising from the increasing throughput of white products needed to keep Nigeria moving by road, air and sea. Millions of tons of petroleum products were to be imported to support flagging productivity as her refineries during the mid-1980s. A New Oil Jetty (NOJ) was to be built to host calling ships, VLCCs and million-barrel tankers. This time the contract was awarded directly to Funq Tai Engineering Company Ltd. The sea bed at Apapa jetty site was composed of many metres of mud, which had to be removed via dredging and disposed off at sea, over three million cubic metres of spoil. In its place, over three million cubic metres of sharp sand was required to carpet the sea bed to form the construction base for NOJ. For the first time in his life, Sir Chuks saw a trailing suction hopper dredger (TSHD) in operation. A fully motorized, self-propelling dredger, the TSHD steamed to borrow pits in the Atlantic Ocean nearby and mined sharp sand up to 7,000 cubic metres at a go, stored it in its cavernous belly and steamed back to dump it at the jetty site. This was repeated many times during the working day until the whole milestones were attained.

Soon NOJ was built for the NNPC, commissioned and put to use; mission accomplished. Though he leased the dredgers used in the NOJ project, Sir Chuks thereafter decided to go into the dredging business, especially seeing that it complemented civil construction. In the next five years, Funq Tai had undertaken some large dredging projects, mainly sand mining and reclamation. It had acquired many dredgers of its own, though not TSHDs; it had leased some and disposed off others. In short, the company had now cut its teeth on dredging as a business. It was in the course of these early years that Sir Chuks met Baltimore Dredges LLC, makers of the Ellicott brand of cutter suction dredgers. The story of this meeting has been succinctly captured in our exclusive interview below.

However, the story of Funq Tai’s dredging activities mirrors the struggle of fledgling Nigerian companies to feed from the same trough as the likes of multinational dredging contractors like Dredging International, Van Oord, Jan de Nul or Royal Boskalis (Nigerian Westminster Dredging and Marine). Will they succeed? All said, many of these indigenous firms emerged within the last decade to play in the small-scale to medium-scale sector of the industry for sand-mining and reclamation, shore protection or well-head sweeping, etc. Have they succeeded? Most are hobbled by teething managerial problems and almost all, by financial challenges, despite the otherwise rich pickings. Even some have now broken the glass ceiling to play in the big league, such as the Nestoil’s B&Q Dredging with Julius Berger et al or even Funq Tai which joined in dredging the Niger. But what is their future?

While the answers are blowing in the wind the expulsion of expatriate hands from Niger Delta dredging fields portends a fine future for those Nigerian firms that manage to get their acts right. Especially in view of the increasing force of the National Content Law in the oil and gas sector which compels the IOCs to give Nigerian qualified firms right of first refusal, the heavens could be their limit. Because, the market for dredging services is now untrammeled; it’s even getting set to boom as part of the emerging market phenomenon homing in on Nigeria despite all odds.

So that, for Sir Chuks and Funq Tai, the Nigerian dredging world might well be their oyster. To get a closer feel of his heartbeat on burning issues in the industry, we sought an exclusive interview where he fielded questions on many varied topics: the early days, Festac Phase II project, River Niger dredging and Niger Delta problems, the poor state of many dredgers in the market, business relations with Baltimore Dredges, the score-sheet of NIWA as the supervising authority for the River Niger dredging project, the new 2% NIMASA cabotage charge on dredging contracts, etc. Excerpts:

On the origins of Funq Tai Engineering company…

Sir Isaac Chuks: The original Funq Tai company had about 2,000 engineers. So, we had a franchise to operate it in Nigeria, that’s how we started.

DDH: What year was this?

Sir Isaac Chuks: 1992.

DDH: Did you come straight into dredging by that time?

Sir Isaac Chuks: We didn’t, but in 1993 we came into dredging because one of our projects involved dredging. We were using hopper dredgers as well. The jobs Funq Tai did after the pipeline laying job was to do the port channel into Apapa Port, we did the dredging to make sure that the vessels pass through that particular channel. And from there we came into [doing] the Apapa Jetty for NNPC. When we discovered that that place was full of mud, we were to dredge and remove over one million cubic metres of mud before we started to bring in proper materials for use in building the jetty. So we brought sharp sand like what they are doing now at the Eko Atlantic City, and poured it into that area to replace the mud which was displaced to the channel. We used a hopper dredger to clear up the mud. What Trevi Foundation discovered during a study was that the water comes in straight to that particular location [from a river], and that’s how the mud was being deposited.

On Funq Tai projects since inception…

Sir Isaac Chuks: After the pipeline [contract], we did a wonderful pipeline job, 3,000-km pipeline with pumping stations, we maintained office in Munich Germany, bigger than this office. We had about forty expatriate professionals. We were working in the NNPC with people like Dr Tabiowo and his people, so we picked up the engineering, vetting the designs stuff for that pipeline project through the company they called ILF. ILF is one of the biggest German designing companies. We vetted tons and tons of engineering drawings, marked it and told them what was right and what was not right. Then we had quite a lot of engineers from Hungary, Austria, Germany, Britain, Nigeria. People like Alex Momoh. So, Funq Tai finished that and after that we came back to Nigeria to execute the project. We started all the way from Port Harcourt, some of my workers started from Uromi, in Delta state up to Minna. You can see the tank stations [pointing at a map]. We were now engineers and engineering consultants, we managed everything: we load and lay, river crossing, welding the pipeline, x-raying all the whole thing, we put up our x-ray depots along the whole area, managed the whole pipeline, tested it, commissioned it, for NNPC. This was when NNPC was working and people were willing to see NNPC work, people like Dr Ihetu and the rest. We did the Kaduna refinery with Chiyoda of Japan but that wasn’t under Funq Tai but under Chuks International, a contracting firm as well. We were working 24 hours a day. The Japanese came with about 1,400 and thirty-something engineers, all experts, no single labourer. The refinery was built in Japan, they configured it, designed it and they shipped it to the place we were doing the installation. All the people they brought were professionals, administrative, engineers, electrical, everything was complete. When they came down [to Nigeria], they gave me [contract] for the supply of all the earth-movement [equipment], the cable works and transportation of all the staff. In fact, by then, I used to run the transport called Chuks International, I gave them all the buses. There is one Tony Ukaasoanya from our place. He was doing the labour contract. That’s how Kaduna refinery was constructed. President Shehu Shagari came to do the commissioning. I just came back from China, you can see this company, SADANE. Sadane is one of the biggest companies I have seen in my life. Four classmates, and Sadane, I can tell you might be something bigger than Caterpillar, owned by four friends. They employ not less than twenty something thousand [workers]. I was there with Mr Ajumogobia, we saw it, very massive factory. Sady wants to bring their equipment, to project their company in Festac Phase II. They said ‘look, Sir Isaac, we are going to give you free equipment. In fact, we make sure that our equipment is working there’. There’s another Ukrainian company partnering with us in Festac Phase II.

DDH: What is this Festac Phase II project?

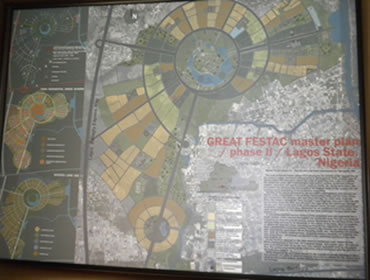

Sir Isaac Chuks: We are going to develop an area of 1,186 hectares of land which our group is trying to sand-fill and develop it like a mini-city. But unfortunately people have already acquired illegally large expanses of that land. We have spent so much money. But as soon as the Ministers are able to get the FEC (Federal Executive Council) approval…. This has been delaying it. All the investors have lined up waiting. Today, am going to talk to the Minister. We are going to build it like a wonderful city, you know there is Phase I, now we have Phase II. One of the biggest Chinese companies they call the North China Construction Company Group, they are one of our partners too. We are going to ask them to design this number of hectares here like this and this number like that there, we are going to have different designs and then incorporate them together. So, they design the buildings, the locations, the roads and whatever and we are going to have a centre.

DDH: Who are the promoters?

Sir Isaac Chuks: Funq Tai Engineering and Construction Company Ltd and and New Festac Development Company, which is a JV company.

DDH: Is the Lagos State Government taking part?

Sir Isaac Chuks: Yes, we are trying to put them in now. We would like to put them into the system so that they regulate certain rules and laws of building and all those things and we may need their help in so many other cases. We will cooperate, the city is in their state, they are the owners of the development; the federal government and us are tenants on the land. We are the owners of the land. We are going to manage the land for 33 years, the maintenance of the roads, electricity, the drains; we are going to get a separate power generation. The people we are going to use for the power, they call them the TBM, they are one of the most efficient power companies in China, they are responsible for over 30% of the whole power in China. They are into the generation of power plus water, that is, windmills. In that area of Festac, there is a lot of wind because of that almost two kilometres of [development] they did there. And that route used to be thunder line.

DDH: Talking about dredging how did Funq Tai cope with the magnitude of the Lower River Niger dredging? You have not done that type of dredging before, have you?

Sir Isaac Chuks: Not that type of job. You know one thing with dredging is that each dredging job has its own peculiarity. As for River Niger dredging, when we talk, we talk the truth. In a project like the Eko Atlantic City being done by Dredging International (DI), for example, they are now using a hopper dredger, Congo River, doing 30,000 cubic metres in a haul. That is, going to the sea, get the type of sand, come to that place and then pump it out, maybe because there is no sand nearby to take from. But there is one technical issue, very interesting. Before them, they had Chinese Harbour Dredging in that place (Eko Atlantic City) and I remember one time they came to work for us in River Niger and they had no dredger that can pump more than 500 metres. But the dredger DI is using here is specially designed so that it can pump up to 5 kilometres via pipeline. This is a peculiar one. But there is another area you can come to and you have your hopper or your cutter [dredger], like what we did in River Niger. In River Niger, there was the sand there, all you have to do was to follow their specifications. What were the specifications? We had surveyed the land, we surveyed the route, we know certain areas that are not deep. Then what is the quantity that we are cutting? We didn’t do more than three metres depth. Three metres is only about nine feet. So, we cut it off to enable some small light vessels to pass. But then along the line, we had agreed, we did about 60 metres wide in the whole expanse of River Niger dredging. And what we did was, by the left, there was already a sand dump, by the right a sand dump. But because of all this over-flooding of the River Niger, which has now been proved for everybody to see, that River Niger is almost three kilometres wide, so when you come, you think that everything is River Niger. So what we did was what we called ‘river dumping’. There was nowhere for us to put our pipes and when you dredge, you would be putting it [on the banks], no it wasn’t like that. What we did was pumping it in by hydraulic sand-filling. When you are hydraulically sand-filling, the sand already is getting compacted, and is stable, it stays. But you will notice exactly what we dredged if River Niger goes down properly; then you can see by the banks all the whole filling. Another interesting thing we did was, there are certain areas you would come into the Niger like this [pointing at a sketch he made], these are the banks. Sometimes, you will see a very big hole here. You have somewhere here you are going to dredge. So, when we trace the hole here, we channel it into the hole and they fill. So as you are moving along the line, when you come to some other places, you pump the sand by the sides. It doesn’t mean that sometimes some part of the sand will not drain back. But that is why we are talking of continuous maintenance. And continuous maintenance is a thing you cannot just do under one year. Okay, if we have done three metres, maybe the next rainy season, that area that is three metres, because of the underground current in River Niger which is very fast, it may even make that place to be about four metres deeper. Water itself can help to remove one metre for you and take it to somewhere else again and drop it off. That is why we continue to do survey work, to tell you exactly what the situation on the base is. After the survey, you will notice that ‘look, my friend, you have to do here and you have to do there, that is the quantity’. That is one point. Then two, the point I want to make clear is that, River Niger, if we start to dredge everything as it is, federal government will probably spend hundreds of billions, which they don’t have to do. Now, the government thought that we can be dredging this thing gradually, and do the maintenance, removing the spots today, gradually, and that is the only way that project should be done. If we go to the River Niger and say ok, we are going to do ten metres, it’s not dredging. You know what we are doing, we are just digging big holes. We are digging unnecessary big holes. Because there’s not even enough water to occupy what we are dredging. See, what I mean. What we did was three metres and there’s enough water to cover the channel. But if we dredge ten metres, this water in the channel now will sink to that depth and not have enough to keep running, you have created a lot of problems here for not only ships but even ecologically. The whole of the banks will now be caving in. But now we have created that 60 metres width, as time goes one, you do another small one, this area has already been stabilized. As time goes on, you do another small one, as much as you think you need to keep to the depth of the vessels that are plying the river.

DDH: You are saying we cannot just dredge to the level we want without considering the water quantity in the river?

Sir Isaac Chuks: Yes, you cannot do that. Now, you see they opened up the dams and River Niger is swollen, because it was not deep enough. The water gathered in the dams was what could have been passing through the river. I heard one gentleman talking, I wanted to reply him but I said I don’t want to waste my time. This guy has no idea about what we’ve been dredging. He said that River Niger is not dredged. That the federal government has to go and dredge River Niger. So, that is where this issue comes in. Now that they released water from the dams, that water has done down to the sea and the river will go back to its normal level. But there is water that has a flow, just like at Apapa port. You know that Apapa port is always filled up. You can dredge Apapa up to 12 or 13 metres deep and that water will still be filled up. But this one [River Niger], the supply is less than its intake, that’s why we have this problem. River Niger depends on weather. When dry season comes, it goes down. When rainy season comes, it comes up.

DDH: What lot did Funq Tai do?

Sir Isaac Chuks: We did lot 1, from Warri to Bifurcation, 200 kilometres. Dredging International did from Bifurcation to Onitsha, etc. Lot 1 is the longest and most problematic lot.

DDH: Why was it the most problematic?

Sir Isaac Chuks: Niger Delta people, etc. At the same time, we have the sea water coming from Warri and the sweet water coming from upstream. We were battling with two different tides, from the sea and from fresh water. So, it’s not exactly the case that what we do at one end is the thing we must do at the other end as well. We adopted different steps and ideas.

DDH: How many dredgers did you use?

Sir Isaac Chuks: We used over four to five dredgers and that was what enabled us to meet up with the deadlines. Because one, why did we use up to four or five dredgers? Like Van Oord and Dredging International, they were lucky, so to say, because they could work day and night. But our location was exactly the heart of the terrible Niger Delta issues. They were killing people, there was a lot of problems, there were pirates. And you think it is a joke, the people will come and attack you, you see the attack. What we did was to try and manage and work from 7 o’clock in the morning to 5 o’clock in the evening. Five o’clock, everybody must go, effectively we dredged about nine hours per day and that did not pay up because of our dredge. Because we leased as many of these dredgers as possible. We did not even bring our own dredgers there because it would expose them to vandalisation, either to sink it or to destroy it. So all we did was, we didn’t put anybody that is an expatriate there. Because the moment they see them they can kidnap or kill them. So, we avoided all these things because originally what was planned to do that job was not exactly what we did. We started to recruit people from the locality, employed them and leased the dredgers. As much as possible, we leased them, managed the dredgers and utilized the dredgers to do that particular job. Because by the time we wanted to get in our new dredgers, our banks did not support us. They said there were a lot of dredgers in Nigeria so are you going to buy some new dredgers? Technically, we put one of our own dredgers we had in Port Harcourt waiting to do that particular job. They took it and parked it somewhere.

DDH: But you were also saying that you are making some new acquisitions of dredgers?

Sir Isaac Chuks: Yes, we are getting about three dredgers from Baltimore Dredges. Then we have two other dredgers, that’s why am going to Israel. We are buying about two brand new dredgers from my partner called Tavurah. But we want to get it into Nigeria on lease, one 24-inch and one 20-inch.

DDH: Where are you deploying that?

Sir Isaac Chuks: You know we have this job in Festac Phase II. We want to do about 20 million cubic metres.

DDH: Where are you going to get that sand from?

Sir Isaac Chuks: You know there was a borrow pit there before. You know they did Phase 1 before. We are trying to use the same borrow pit, in continuation of what we want to do.

DDH: Do you think there is enough sand to make up that quantity?

Sir Isaac Chuks: We shall excavate the soil, the soil is sand from top going down. So if we excavate up to 16 metres, we get all that we need. We shall use that to sand-fill that location and use some to build as well.

DDH: Now, Baltimore Dredgers is the maker of the Ellicott brand which you said you brought to Nigeria? Did you really?

Sir Isaac Chuks: Of course, yes, I did. Mr Peter Bowe is the president of Ellicott and Paul Quinn was one of the directors; well, Walter came later. But we met so many years ago in Baltimore when I wanted to buy a dredge. When I met them, I suggested to them to look at the Nigerian market, that if they come to Nigeria with the EXIM Bank, that they will succeed. That actually Nigerians needed dredgers but they didn’t have the money to fund it, and that a lot of people would like to go into buying dredgers through them if they could help in funding, the same thing I was trying to do. So they actually came on board with that idea. Paul came to Nigeria. The first time he came it was like ‘this hopeless country where there is a lot of criminals and everybody is killed on the streets’. I never blamed them actually because America wasn’t as bad as that as a society (general laughter). Because [in Nigeria] people were kidnapping and there was a lot of kidnapping of white people in the Niger Delta. So, when Paul came there was a lot of police and soldiers. The American embassy had to send a lot of police to follow him up and down. But by the time Paul went to Port Harcourt and he went to places with the police and everybody, he discovered actually that they don’t kill every day. That it happens almost all over the world, you know. The percentage of criminals is like 0.5 percent; all these troubles that you see happening, just 0.5 percent of the population, the same thing that is happening all over the world. And they found out I was telling the truth and that I wasn’t 419. They were saying Nigeria was full of 419ers, but I said, well, as far as am concerned am not 419. And we still have so many people like me in Nigeria who are doing their legitimate businesses. So come around and look around yourself. When they came they went around from Lagos to Port Harcourt, even up to Bayelsa and saw that there were no wolves on the streets. He went back and made his report and they started to come. Believe me they wrote about me in an American magazine, 6-pages, where they were praising Sir Chuks who brought them to Nigeria. But today, they have sold so many dredgers, the 12-inch dredge, 14-inch dredge, 20-inch dredge and their shipyard has expanded and they opened up a new branch in India and China and every other place. So, they are the people am buying the three dredgers from.

DDH: How is Funq Tai doing as a company, financially, operationally, your vision…?

Sir Isaac Chuks: My vision is a very large vision, you can see all these. We are supposed to have a serious investment in Festac Phase II, proposed to be up to $7b. We have very big companies like North China Construction Company Ltd coming to start with up to 100 hectares. By the time we have up to 1186 hectares, we are going to make a new city away from Festac Phase 1.

DDH: How are you disposed to our new association of dredging stakeholders in Nigeria?

Sir Isaac Chuks: In fact, am not even talking of only about association, we are supposed to get the Nigerian contractors association, who will be very strong, speak out and determine their fate.

DDH: I was going to ask you about the high cost of getting the contracts and the huge sums spent to chase payments for finished contracts?

Sir Isaac Chuks: That is why they don’t give you a proper job because of the level of corruption, people now have turned to be contractors, there is no more due process. That is why my company is thinking to diversify into some other daily money yielding stuffs. We want to build hotels, industries, things that will [enable us] control our destiny.

DDH: So, dredging as a business is being endangered?

Sir Isaac Chuks: Dredging, if you are talking of dredging, for example, the realistic dredging companies and people I know, they are very few. So many other people are making experiments, coming on board. A lot of the dredgers that are in Nigeria now, they work two hours, they spoil for five hours. If you realistically make a census of proper dredgers in the country, they are very few, who can be able to give you dredgers and you have a plan and their work is done according to the plan, they are very few. And that is why everything we are getting is brand new, three 24-inch dredges and one 20-inch dredge.

DDH: But if Nigeria had a maintenance culture it will help…

Sir Isaac Chuks: Yes, at a time, we even thought we were going to establish a dredge maintenance workshop where you can service your dredgers. We would have a very big tug boat, if you are in Port Harcourt, we can tow it for you and bring it down to Lagos, refurbish it, turn it around, paint it, change your engines and make it to look new. But again, dredging in Nigeria is a continuous project. Just like roads, we have to continue to develop our waterways, like what we have done in River Niger. River Niger is still going to be dredged for the next twenty years.

DDH: But is it viable? Are there commercial ventures to pay for it?

Sir Isaac Chuks: Of course, why. Let me tell you, for example. It’s like we have done about 600 to 700 kilometres, from Warri to Abuja. A road network of that magnitude that can take such vessels from Warri to Abuja will cost you so much billions. For example, from Abuja town to the Airport, Julius Berger charged you over N56b and people thought it is too much. It could be N60b to do that road. There is some quality you would put there and it would take you about N100b. Now if it cost about N60b from here to Abuja Airport, you can imagine what it would cost, the same flow of vessels just like the cars, to go all the way to Warri by road.

DDH: It was announced to have cost N32b?

Sir Isaac Chuks: Well, the N32b was just to dredge to that level to contain barges and all these kind of stuffs. But by the time we continue, if this dredging is done for the next ten years, my estimate and the estimate of NIWA is that each year, you do about two metres and maintain the channel. Then after all these for about ten years, you take an average of say 10 metres for the next ten years. Then the stability of the shoreline, and the stability of the excavation and the stability of the flow, it continues gradually.

DDH: How much is the cost of that?

Sir Isaac Chuks: Well, if you do that for about ten years, if you are going to dredge the River Niger, for the whole routes, maintenance, and have about N8b every year, that is N80b. it is worth it, it will pay back itself and vessels will start using it. The ports they built, if people start using them, and move their goods from one end of the country to the other, it will pay off.

DDH: In other developments, NIMASA is announcing the payment of 2% of dredging contract sum by dredging contractors on awarded projects as part of cabotage law implementation, what is your take on that?

Sir Isaac Chuks: They should not tax anybody. If I have a project, and I pay VAT and tax, why should I pay 2% again? It’s like the rubbish they do at the ports, charging for things they are not supposed to charge for. They should look for more positive ways to derive funds and not sucking people’s blood. The point am making is that I will not pay. If I have a tender, a project I want to give to someone, you can’t tell a dredge owner not to tender for my job, that I must pay 2%.

DDH: What if you are required to include it in your tender, so that it is deductible like VAT…?

Sir Isaac Chuks: Then, that is what they can talk with federal government, federal ministry of works and all the others. They can tell the owners of the projects that look if you want to work in the water, they should come through NIWA because NIWA is the owner of the inland waterways. For cabotage law, they should go ahead and fund vessels, they should go ahead to support you to buy vessels? Do you support dredge owners to buy dredgers? Are you now equitable owners of the dredgers you buy? If you have supported people to buy vessels, you go on the vessels. If you apply, we pay you 2%. If you have nothing to do with me, you have not contributed to what am doing, and am working in the waterways and paying NIWA, and am paying the people for whatever things I dredge, why should I pay you 2%? I will go to court.

DDH: Finally sir, how did NIWA perform as the representative client and administrative agency for the River Niger dredging?

Sir Isaac Chuks: To be frank and candid, NIWA still needs to be modernized. They still have to put things in modern ways of governance and administration. What I saw there is that they are still ten years behind, in the areas of equipment, in training, in the areas of what they have like vessels and so many things. They are still holding onto what they held many years ago. They need to change so many things. Government needs to make a lot more investment into NIWA. NIWA has to change. Just like Nigerian Railway Corporation, which has been changed to modern railways. NIWA has to change to modern inland waterways management. They have to see what is happening in America, what is happening in other countries, Ukraine, China, Israel, etc. How do they manage harbor management, inland waterway management systems? How do they collect revenue? How do they manage the channels and all those things? By the time we did the dredging really, the capability, they tried actually, but in the engineering, most of the work was lumped up in one man’s office, the general manager, engineering. You see piles and piles and piles and I was asking why? He said that some of them are not competent to handle some of the work? So, that’s how it turned out to be a one-man’s show. Our invoice which was supposed to be paid by December is not yet paid up till today. Sometimes when the invoice is ready the managing director has travelled. Before they sign the invoice, it takes so many weeks. So, that’s the kind of management [for the River Niger dredging]. We need to change it. If it is not taken like a private company, we are wasting our time.