By Edmund Chilaka

The first incarnation of the Akpomejero clan in Nigeria’s sand mining industry was a rollercoaster. Perhaps, it was the lack of sound technical knowledge or the want of good advice, but the venture, Madodel Engineering Construction Ltd, became vulnerable to bad business weather. Although it was floated by an acclaimed finance guru, Steven Oghenevo Akpomejero, in 1992, the business was afflicted by failed collaborations, faulty partnerships, litigations and arbitrations for the better part of its corporate life. When his son, Batare, took over as chief executive in 2001, the last series of arbitrations with estranged business partners was ongoing. Although he witnessed its conclusion, the aftermath was unfavourable for the young company as its operations were rendered helpless, illiquid and disoriented. Batare picked up from the ashes and re-engineered the business focus, and experimented with the patent small-scale Chinese dredging model. It paid off. He also re-jigged the management and board directorship of the company which gained moral capital for their operations in Lagos state. Thus, in six short years, he re-modelled the venture and incorporated the second generation of the Akpomejero business plan in the dredging and sand mining sub-sectors with the outfit called Rockston Dredging and Allied Works Ltd. However, the story of Madodel Engineering Construction Ltd fits perfectly into the narrative of the indigenous pioneers of dredging activities in Nigeria which we tell in this special edition. The story, narrated by Batare during exclusive interviews for this edition, is useful for the education of readers and dredging practitioners about the crucial precautions for all operators or aspiring operators, to know the pitfalls of the industry, especially the indigenous section. Some of the names of the major actors have been withheld or changed for legal reasons.

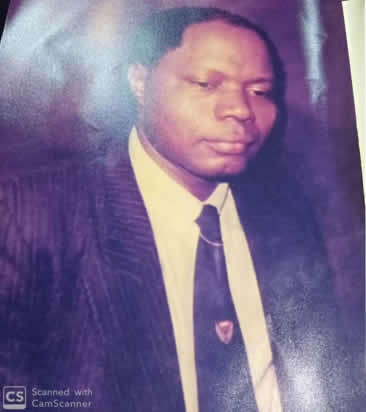

When the senior Akpomejero worked at the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) from 1968-1974, he was a contemporary of Mr. Joseph Sanusi, the former Governor of the Bank, and a few others whose life paths were to cross again during his post-retirement endeavours in the sand mining sub-sector. A chartered banker by profession, Akpomejero began consultancy services when he retired in 1989. He managed financing packages for dredging and sand mining companies and found that he made more money through this than he ever made during his working life at CBN and for other banks. One day in 1992, someone brought him a proposal for a large commercial sand dump at Majidun Ikorodu. The project was to stockpile 1m cubic metres of river sharp sand for sale to the public, the popular pump-and-sell market. This was the first project being handled by Madodel Engineering, his startup. The financing was handled by the consortium of insurance companies led by NIDB. Harris was contracted to stockpile the first tranche of 200,000 cubic metres. However, after pumping about 21,000 cubic metres, Harris suddenly stopped work and demobilized its dredger. It had just won a contract with the Lagos State Government and decided to leave. Madodel viewed this move as a breach of contract and sued for damages as well as to prevent the dredging firm from moving the rest of its dry plants which would leave the project site haphazard and helpless. Despite strong pleadings in court which allegedly elicited favourable pronouncement for Madodel’s cause, a reversal was in the offing after all. A few days after the court ruling in their favour, bailiffs from the same court came to Madodel’s office and began moving property and equipment with the claim that the judgment papers issued after the case blamed it for the impasse and levied costs against it. In the end, there was no respite and the company lost out in the deal and discontinued with Harris.

Two years later, in 1994, Madodel entered another contract with Ham for series of stockpile campaigns beginning with 100,000 cubic metres of sand. All went well with the project and was followed by a second campaign of 100,000 cubic metres. As the project progressed, however, news reached Ham that one of the stakeholders in the Madodel joint venture was secretly financing another sand mining company, a close Madodel competitor, to pump 250,000 cubic metres of sand using the services of Westminster, a competitor to Ham. Unhappy with this apparent conflict of interest, Ham decided to halt further sand mining for Madodel. It saw the clear betrayal from inside Madodel and lack of common purpose for one of its partners to finance its competitor to patronize the services of a rival dredging company. Consequently, it demobilized from site and removed all its equipment: the dredger, embedded pipes and dry plants. Rankled by this seeming betrayal, Madodel wrote the NIDB and listed all the facts as they have become known which showed that the partner was at the root of the failure and loss of the project and the sudden withdrawal of Ham from the project. Subsequently, the joint venture broke up and all parties went their separate ways.

Next Mr. Akpomejero approached a Lagos-based investment company which for the purposes of this story will be called Company M, which played a very crucial role in the activities of Madodel for many years thereafter. Company M agreed to come into the joint venture on the basis of 55% for Madodel, 40% for itself and 5% for the facilitator. For this phase of the sand mining campaign, Madodel had arranged with Nigerian Dredging and Marine (NDM), a Dutch company, to do the stockpile. However, while preparations were underway for NDM to mobilise to site and begin the operations, Company M introduced its trusted financing firm, IFL, as a financier. The coming of IFL into the venture catalyzed in a change of the chosen dredging contractor, NDM, in favour of a Port Harcourt-based Nigerian dredging company which had prior relationship with IFL. Unbeknownst to Madodel’s management, the recommended dredging company was owing the financier money in connection with a previous contract. The financier thought by this move to recover its money while the dredging firm hoped to defray its indebtedness by deploying successfully at the Madodel project site.

Madodel reluctantly accepted the change in favour of the Port Harcourt-based firm. However, it failed to perform and could not deliver the agreed quantity of sand due to the constant breakdowns of the dredger; it was under serial repairs for most of the times. After six months of lackluster performance, the Nigerian firm demobilized from site leaving Madodel to pick up the pieces. Thus, dissatisfaction in Nigeria’s mechanized sand mining industry could stem from many factors, including disputes about quantity pumped, failure to attain agreed milestones, disruption due to failed equipment, poor performance, betrayal of trust, breach of contract and various disagreements among partners and clients, etc. Overall, this poor state of affairs seemed predominant among indigenous dredging firms. Being a new business niche for Nigerians and with the poorly developed state of jurisprudence and law enforcement in the country, the pioneers of Nigeria’s indigenous dredging industry experienced a rough business terrain, even though the sub-sector was lucrative.

In 2001, the partnership between Madodel and Company M continued and another dredging contractor, Gaytech, headed by the late Dr. Anthony Okorodudu, was invited to work on stockpiling sand at the Madodel site. After working for four months, Gaytech also demobilized from site following irreconcilable differences. Subsequently a dispute arose between Madodel and Company M about ownership of the 20-acre Madodel site. Although Madodel made had made initial payments to the Asajon family on the land, some members of the family began to ask for fresh payments, claiming that the land had not been paid for. Payment for the land itself had been a subject of controversy. At first, the family had agreed to sell 24 hectares to Mr. Akpomejeroh’s at the rate of N70,000.00 per hectare. His plan was to reclaim the land gradually use some part of it for the sand mining business while the rest would be developed as an industrial estate for few large firms. However, when he got ready to pay for the rest of the land, the family revised their quotation and insisted that the agreement was to sell at N70,000.00 per acre, more than double the original agreed price. This was the first instance of disagreement. When it was settled, Akpomejeroh made further payments totaling N1,680,000.00 through the wife of one of Madodel’s directors who was a son of the soil. To the initial cash payment of N70,000.00, a bank cheque of N1,610,000.00 was issued to the family during the 1990s.

Much later, however, after the failed sand stockpile campaign by Gaytech, disagreements again surfaced amongst the partners as Company M began to claim the ownership of the land, citing a sum of N1.5m sourced from IFL which was also used to pay for part of the land. However, Madodel discovered that a lot of intrigues was involved in this new dispute hatched by some of the directors and partners in the business who were seeking personal aggrandizement. They went to the extent of denying that Madodel had made any payments for the land. To this allegation, however, some of the Asajon family members countered them by admitting that some payments had been made to the family. Company M capitalized on the allegation that Madodel had not paid for the land to demand that the partnership sharing agreement should be amended so that 55% should go to it while Madodel’s share should be reduced to 45, with the facilitator remaining unchanged at 5%. Madodel refused. When the matter had festered for some time, it was agreed by all parties to go for arbitration, with Chief Emmanuel Adetunji chosen as the arbitrator. Mr. Akpomejero had trusted Adetunji, the arbitrator, because they had known each other well. Adetunji was Akpomejeroh’s boss when they worked together for many years in the accounts department of the Central Bank of Nigeria. Nevertheless, inter-locking board room appointments have linked Adetunji in other ways to the present business. Adetunji had become a director of IFL, Madodel’s financing firm, in a former capacity as Managing Director of an insurance company holding shares in IFL. In view of the crucial nature of this arbitration, Batare was pressed to the fore of the arbitration meetings and attended all the sessions which held in three months starting from June 2001.

On 24th September 2001, after several months of arguments and counter-arguments, Adetunji delivered a decision which Madodel considered crippling. According to the ruling, the two parties in the case were told to actualize their claims on the disputed plot of lands by redeeming the full value to the family. Usually arbitration judgements are largely binding on the parties; by convention, they are rarely contested. For Madodel, the financial implications of redeeming the full value of their claimed portion of the land ran into several millions of Naira which was beyond the company’s immediate financial capacity. Needless to say, the dispute weakened the spirit of partnership between Madodel and Company M and the situation largely resulted in the senior Akpomejeroh’s gradual exit from active sand mining and dredging business. Thereafter, Batare, being the first son, decided to take the future of the company in a new direction. Although the pioneer eventually supported his son’s vision to re-strategize the company’s overall business plan, he did not live long to see the fruition. He died in 2004 just as his son’s new vision began to yield fruit.

The Next Generation

Batare told DDH that the experience of his father’s difficulties with partners and associates in the dredging industry was painful and proved decisive for him. In retrospect, he felt that the series of litigations and arbitrations (some of which he witnessed from 2001), were avoidable with better business planning. Therefore, he decided to take the outfit in a new direction. At the time, the Chinese dredging technology was yet to be tried in Nigeria although the idea had been swirling around. Moreover, other developments had begun to indicate winds of change about to hit the sand mining sub-sector. In Lagos, the State’s Ministry of Infrastructure and Waterfront Development began to give notice to dredging companies to relocate their burrow pits beyond 1,000 metres from the shoreline. For users of European and US dredgers, this would involve huge expenditures to comply. Thus, Batare decided to try the Chinese model. This involved a mother dredger working midstream and pumping into transporters which convey the same to the shoreline or the sand fill. He sought a joint venture partnership where his equity contribution would be the Madodel owned land, the company’s cadastral license for sand mining, liaison with local authorities and good will.

Armed with this arrangement, he signed the first partnership agreement in 2002 with DESUAN Nigeria Ltd. According to Batare, his company was the first time to use try the Chinese dredging technology in Nigeria. In practice, the Chinese partner brought one dredger and two transporters and the business was on at the Madodel site in Ikorodu. The sand stockpile proceeded as projected while the companies shared profits as agreed. The partnership worked well until DESUAN overloaded its side of the business by going into quarry prospecting. Quarrying is even more financially demanding than sand mining with the Chinese model. DESUAN was using its share of the sand mining income to fund the quarry and because of this over-spread of its meagre resources to cover dredging and quarrying at the same time, the company burned itself out without succeeding in any of the two ventures. However, for Madodel, the beauty of the partnership was that each partner’s risks and losses were limited to its commitments in the venture. So, Madodel suffered only slightly from the miscarriage of the DESUAN joint venture when it came to an end.

Batare said he gained a few things from the failed DESUAN venture, including the fact that it confirmed that the Chinese dredging model was viable if properly managed. This gain emboldened him to go into the second partnership agreement. This was signed between Madodel and Golden Silk Industries of China in 2007 and the business did well. Beginning with four transporters, Golden Silk increased the fleet to 12 transporters. It also registered a local arm of their firm called WAIDA Nigeria Ltd to manage the venture. The partnership agreement was the usual one: The Chinese partner brought the equipment while Madodel provided the land, licenses, goodwill and enabling environment such as liaison and compliance with guidelines of the Lagos State Government, federal regulatory agencies (such as NIWA, MMSD, Federal Ministry of Environment) and the host communities. This venture yielded more fruit than the first, and prospered vibrantly. By 2009, Batare began the second phase of his new business plan. He first registered Rockston Shelter Ltd, then Rockston Dredging and Allied Works Ltd. His plan was to diversify into utilizing the products of dredging activities for real estate development and building construction complements such as molded concrete blocks. Towards this end, he acquired a 12-inch DSC Pitbull dredger in 2009 under the name of Rockston Shelter, for the purposes of dredging contracts and services in other sub-sectors. In 2014, he added a 10-inch DSC Wolverine dredger to the Rockston Shelter fleet. Unlike his father who was cumbered with business relationship issues, Batare adopted different methods, and largely foreclosed on such problems. He attended Obafemi Awolowo University where he graduated with a B.Sc in Urban and Regional Planning. He is also an alumnus of Lagos Business School (2013 set) and Strathmore Business School Kenya (2013 set), where he majored on leadership techniques. In 2017, he became the President of Dredgers Association of Nigeria. His social group activities include patron of Ikorodu Golden Lions Club and Urhobo Unique Brot